Full name

Jan. 11th, 2022

◆

5 min read

At a glance, tokenization seems to be converging toward a single destiny. Every headline sounds identical, like another asset “brought on-chain,” another “world-first” in digital securities. But beneath the buzz, these announcements describe vastly different realities. The term tokenization has become a catch-all, stretching to cover everything from cosmetic digitization to fundamental system redesign. The result? Confusion disguised as progress.

We know that headlines love simplicity, but that results in rewarding narratives that promise transformation without complexity. Yet tokenization isn’t just one story, rather it’s three, each with distinct infrastructure, legal standing, and implications. The future of finance isn’t being written by a single model but by competing philosophies about what “digital” really means.

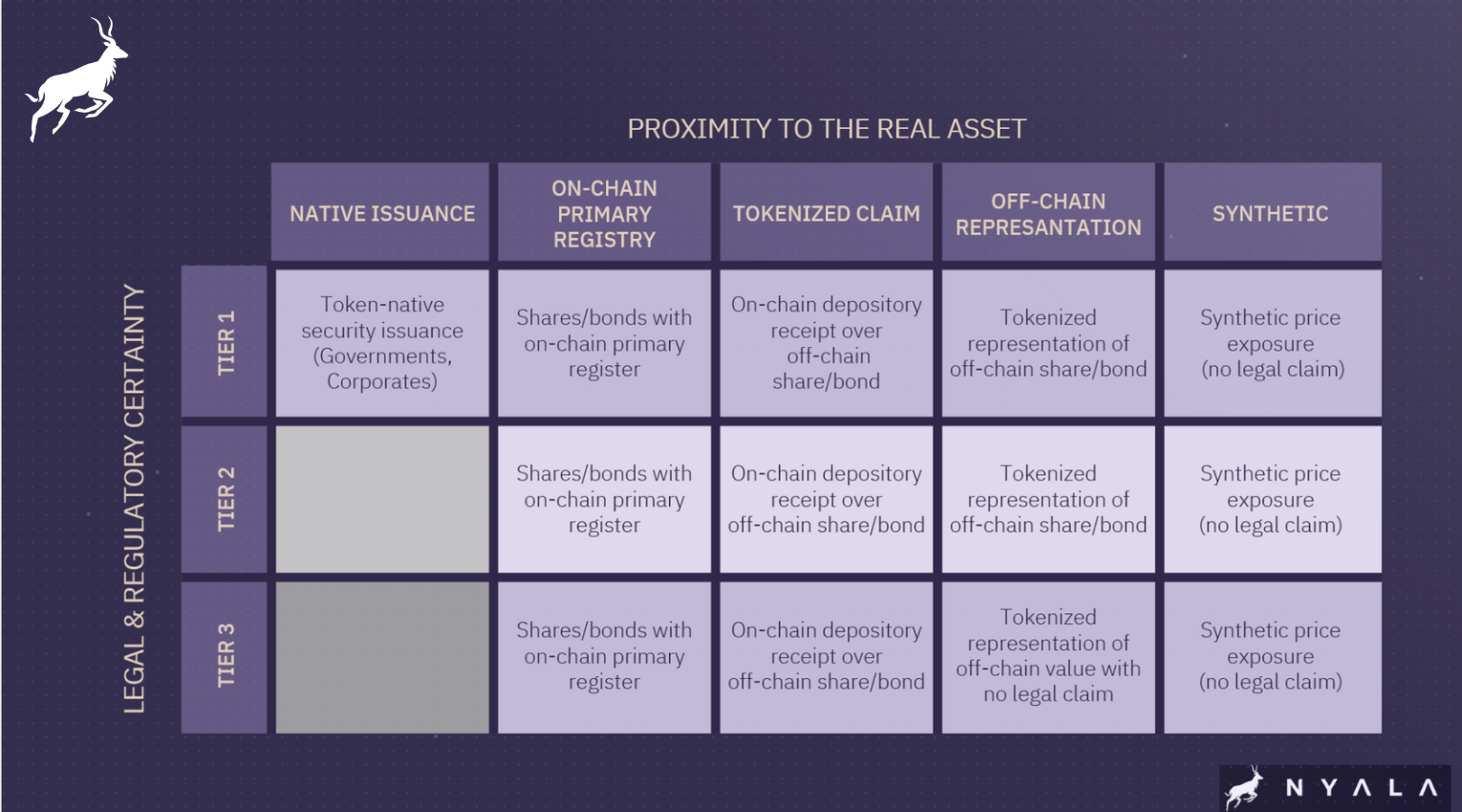

To make sense of this landscape, it helps to sort tokenization into three broad models: representational, synthetic, and native. Each answers the same question, which is how do we bring assets on-chain? But in profoundly different ways.

Understanding which model is in play is not a matter of semantics, rather it simply It defines who holds rights, where risk lives, and how much efficiency or transparency is actually gained.

Representational tokenization is the easiest entry point, also the most superficial. Here, a traditional security such as a bond or share is issued through the usual channels, and then a blockchain record is created to mirror ownership. The token reflects the real-world asset but does not replace it.

This approach has institutional appeal, since It preserves existing legal frameworks and keeps regulators comfortable. Custody and settlement remain unchanged; the blockchain merely displays ownership more transparently. It’s a digital veneer on top of analog infrastructure.

The limitation, however, is structurale, since the blockchain isn’t the source of truth, it can’t automate lifecycle events or eliminate intermediariee, rather as described above It’s a surface layer, not a backbone, which is pretty much a facelift rather than a rebuild.

Synthetic tokenization takes a different route, because instead of linking directly to a real asset, it creates tokens that behave like one. Think of it as a mirror image where investors get economic exposure to an underlying bond, stock, or commodity, but without holding a legal claim to it.

The upside is accessibility, meaning synthetic tokens can open exposure to assets that would otherwise be restricted by geography, cost, or regulation. But this freedom comes with a catch: trust. Because these tokens depend entirely on the issuer to honor performance and maintain correlation, investors rely more on credibility than legal enforceability.

It’s a model that democratizes access but distances investors from the underlying reality. Here, what you gain in reach, you lose in certainty.

Native tokenization is the purest form of tokenization, the one built entirely in digital space. Here, the asset originates on-chain. Issuance, custody, and lifecycle events all live within blockchain infrastructure, with no off-chain equivalent.

This design unlocks real advantages, for examaple lifecycle events such as interest payments or voting rights can be automated through smart contracts. Transfers settle instantly. Issuers gain efficiency, lower costs, and faster time to market. Investors gain fractional ownership and full transparency.

Crucially, native tokenization doesn’t just digitize finance, but it redefines its architecture. Ownership becomes programmable, actions auditable, and participation global. It’s not an overlay; it’s a reinvention.

Using the same word for all three models conceals the real stakes. Representational tokenization maintains legacy structures. Synthetic tokenization shifts reliance from law to trust. Native tokenization embeds both rights and rules directly into the technology.

These distinctions determine who truly owns an asset, how regulators oversee it, and whether operational gains are real or rhetorical. A lack of clarity blurs accountability, and in finance, ambiguity is the enemy of trust.

For issuers, the model chosen decides whether tokenization is a branding exercise or a fundamental shift in operations. Representational systems offer comfort but little transformation; native systems demand deeper change but deliver lasting efficiency.

For investors, understanding the model is essential to knowing what they actually own. A token that “represents” or “tracks” something isn’t the same as one that is that thing. The difference defines both rights and risks.

For regulators, each model requires a distinct framework. Synthetic tokens may resemble derivatives. Representational ones fit under existing securities law. Native tokens challenge the boundaries of both. Oversight must evolve to match the underlying design, not the headline label.

The future of tokenization won’t be built by technology alone but by understanding it. Clarity is the foundation of trust between the issuer, the investor, the regulator and the market. Recognizing that “tokenization” isn’t one idea but several distinct models is the first step toward that trust.

Hype has its moment, but precision endures. The more we separate language from marketing, and substance from surface, the faster we can build financial systems that are truly digital, not just digitally described.

Book a call with our expert.